We have all had the experience of “hitting the funny bone”: that painful buzzing, tingling, and numb feeling in the pinky finger when you hit the wrong spot on the inside of your elbow. Fortunately, it usually takes a few minutes for the feeling to go away on its own. But what if the same feeling started without an injury and it doesn’t go away on its own? At first, you might think that you just slept on your hand wrong, and it simply needs to wake up. But if the symptoms continue for a few days, you might search the internet for an answer to the question: why is my pinky numb?

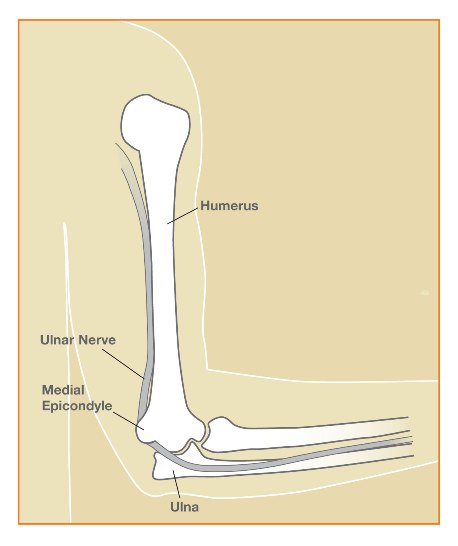

First, a quick anatomy lesson: The ulnar nerve is responsible for the feeling, or sensation, in the small and ring fingers. This important nerve also controls many of the small muscles within the hand responsible for fine motor control and some muscles in the forearm used for strong gripping. The ulnar nerve is made up of small nerve fibers which exit the spinal column in the neck and travel down the inside of the arm. At the elbow, the ulnar nerve curves around the back of the bony bump within a tunnel on the inner part of the elbow. This bony bump is called the medial epicondyle. The ulnar nerve is close to the skin and vulnerable to injury in this location. This part of the elbow is called the cubital tunnel. You may have recognized this area as the “funny bone,” because bumping the nerve here causes that painful buzzing and tingling feeling shooting into the hand. Additionally, if too much pressure is placed on the nerve over time, the nerve is said to be “pinched” and similar symptoms may develop gradually. In addition to hand numbness, some patients experience decreased grip strength and fine motor control (dexterity) making the hand feel “clumsy” to them. In severe cases, muscle loss (atrophy) in the hand and forearm can develop.

The ulnar nerve can be “pinched” or compressed anywhere along its pathway – from the neck to the fingers. The most common location for the nerve to be irritated is within the cubital tunnel of the elbow. This problem is known as cubital tunnel syndrome. However, the nerve roots in the neck and the ulnar nerve in the wrist are also sites of potential problems and can cause similar symptoms.

In any case, if you have numbness, tingling, pain, or weakness in your hand, tell your doctor about it. There are many different causes of numbness and pain in the hand, and problems with the ulnar nerve are not the only culprits. You may be referred to an orthopaedic surgeon or hand specialist if your symptoms do not go away on their own.

You may ask, “Why should I see an orthopaedic surgeon if I have a nerve problem?” Well, orthopaedists don’t just fix broken bones. We take care of a variety of problems including arthritis, injuries to muscles, tendons, and ligaments, joint disorders, sports injuries, and nerve compression syndromes – in addition to fixing broken bones. We can evaluate the problem, try to determine the cause of the symptoms, and develop a treatment plan with our patients.

Fortunately, many patients with cubital tunnel syndrome can be treated successfully without surgery. Options include resting the elbow, activity modification, night splinting, and nerve gliding therapy. Surgery to reduce pressure on the nerve may be recommended in severe or long-standing cases which do not improve with conservative care. Two of the most common procedures for cubital tunnel syndrome are described below:

- Simple decompression: The least invasive procedure is known as an “in situ release” or a “simple decompression” of the cubital tunnel. This procedure decreases pressure on the ulnar nerve by removing tight bands of tissue on the nerve. During surgery, the “roof” of the cubital tunnel (Osborne’s ligament) is divided through an incision on the inside of the elbow. The nerve is allowed to remain in its natural groove within the cubital tunnel. Care is taken to ensure the nerve is free from compression at the end of the procedure.

- Anterior Transposition: An ulnar nerve transposition decreases pressure and tension on the ulnar nerve by shifting the nerve’s course as it travels around the elbow. During surgery, the ulnar nerve is moved out of its groove behind the medial epicondyle to the front of the elbow (anteriorly). After a transposition, the nerve does not need to make the tight corner behind the medial epicondyle, and tension on the nerve is reduced. At the conclusion of the procedure, the nerve is positioned in a bed of tissue either under the skin, within muscles, or beneath muscles of the forearm. These procedures are known as subcutaneous, intra-muscular, and sub-muscular transpositions, respectively. The incision used for this surgery is usually larger than for a simple decompression and recovery time can be longer.

There are similar outcomes in patients when comparing simple decompression with anterior transposition surgery. I favor the less-invasive “simple decompression” procedure for most patients, as this procedure has a lower complication rate. I will perform a nerve transposition if the need arises during surgery, such as when the nerve is unstable within its groove (subluxation of the nerve). This approach has been supported by recent published studies. Please watch video below for more information.

The image and video is copyright American Society for Surgery of the Hand.